“Not everyone needs to be saved. You should know that by now.”: Alone in the Dark 2024

Alone in the Dark by Pieces Interactive, images by me

The original Alone in the Dark is commonly credited with the creation of the survival horror genre; but, like most gamers that developed a love for fixed cameras, tank controls, and item management in the mid-nineties, I jumped straight to Resident Evil. Leon and Claire’s escape from the Raccoon City police station is one of the cornerstones of why I’m obsessed with video games. I circled back around to its predecessor with the release of Alone in the Dark: The New Nightmare but by then it had already inherited many characteristics of its more popular cousin. Like Resident Evil 2, it came in one of those sexy, chunky PlayStation cases reserved for games with multiple discs–but other than some gorgeous prerendered backgrounds and impressive weather and shadow effects, my only memory associated with it is that it contains a 40+ page document which you’ll need to at least skim if you hope to absorb the lore (this document is conveniently placed in the mansion’s library, ten feet away from a dialogue trigger that states “I don’t have time to read”).

I eventually crossed paths with the franchise again at the height of my hunting for platinum trophies on the Ps3. Alone in the Dark 2008 was meant to act as a reboot and had series regular Edward Carnby burning “evil” trees in a semi open world Central Park (it was also developed to show off all the bells and whistles of a fancy new engine). Electricity leaps, flames spread, and you examine gashes in your torso from a first-person perspective to guess at the status of your health. I think I’d appreciate 2008 and all of its strange systems more now, but like The New Nightmare, as it stands, its lasting legacy for me is a YouTube compilation of some of the dumbest dialogue ever spoken in a video game. Also, if I ever needed to catch something on fire, it was easier to stand directly in the inferno–flames rolling off my long coat like a heavy rain. If I remember correctly, all melee attacks were assigned to a control stick, so making slow sweeps with a chair or a two-by-four through fire felt as accurate as buttering bread with a toothbrush.

This probably sounds like I’m nitpicking or judging the past entries too harshly but it’s honestly the space in my gaming history that they occupy. Any narrative twists have long since been overshadowed by an avalanche of weirdness. I don’t necessarily think this applies 1:1, but my trips to Central Park and Shadow Island are not that different from watching a “so bad it’s good” movie–the sort that spawns inside jokes in your friend group for years to come. They’re remembered fondly–but maybe not for the reasons the creators intended.

When I saw that yet another reboot was announced, naturally, I was curious what direction this one would take. I was also immediately onboard because (and this is mostly thanks to Resident Evil, as well), I’ve never needed much convincing to play anything that’s even a little spooky. If the reviews from the larger media outlets are to be believed, it’s supposed to be pretty good.

Alone in the Dark 2024 (which I will refer to simply as Alone in the Dark from here on out–any remaining comparisons will be to other contemporary titles) offers dual protagonists: Edward Carnby (played by Stranger Things’s David Harbour) and Emily Hartwood (played by Killing Eve’s Jodie Comer). In addition to their voice acting, the development team went full Kojima and scanned their likenesses. The bulk of the marketing material leading up to release put the cast front and center. I initially felt this was a bad sign, like the team was spending time and resources on something flashy with little to no impact, but in practice I didn’t find it distracting and their charisma goes a long way towards selling the plot. For my first run, I decided to go with the big man himself. After all, we had a history.

The game opens with Emily on a long drive to retrieve her uncle Jeremy from a sort of estate turned sanitarium named Decerto in the Deep South. Carnby, who she hired back in New Orleans to act as extra muscle, is along for the ride. Upon arrival they discover that Jeremy is missing and finding him is going to be more complicated than wandering the bayou and fending off alligators. As the clues gradually reveal themselves, things get darker and increasingly Lovecraftian.

The story is primarily told between notes, journal entries, and dialogue trees with the various Lynchian residents of the sanitarium. It can’t be overstated, there is A LOT of talking and all of it, from the objectives to the documents, is fully narrated. You can practically taste the accents the actors have chosen for their respective roles. However, these scraps of narrative aren’t a strike against Alone in the Dark. After all, the monologues are optional. You can mute the dramatic readings or exit the menu at any time. I found it’s one of the stronger things that differentiates itself from recent Resident Evils. The memos scattered across Racoon City are usually there to clunkily foreshadow a boss or provide a code for a nearby safe (ironically, the one time the notes do provide dirt on a boss, your character conveniently forgets and starts stabbing randomly to avoid its weak point–exactly three times, because video games). They don’t do the heavy lifting and they’re not what makes that series special. In Alone in the Dark they create a sense of place. We’re detectives. We’re investigating.

That lingering flavor that laces these drawls is overwhelmingly of tobacco. Not since Metal Gear Solid 4’s install screens has a game had such an emphasis on drinking and smoking. Alone in the Dark is attempting to be a noir and it’s clinging to those hardboiled bones–but each flick of a lighter or strike of a match still made me chuckle. Almost every exchange, regardless of circumstances, is punctuated with some vice. Is it time to question a child? I’m going to need to light up to get through this one.

The interiors of the estate that make up the majority of the runtime would be at home on the PlayStation 2. Not graphically, the assets aren’t chunky and the textures aren’t grainy, but the layout contributes to a sense of emptiness. Some areas are littered with stacks of old books and overgrowth, but others contain a bed, a desk, and miles of floor space in between. I don’t doubt that the inhabitants of Decerto live in these spaces, but I also find it believable that they’d regularly look for excuses to not spend any time in their quarters.

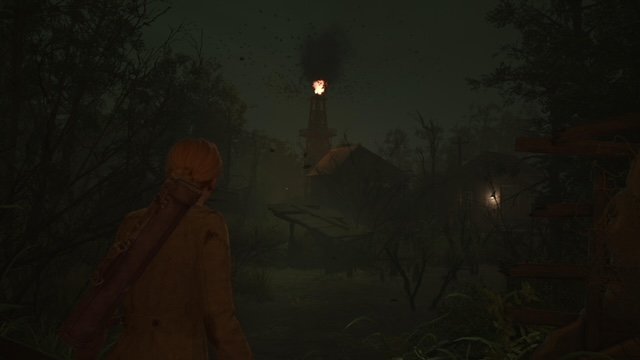

As you explore the mansion (which you do by completing slide puzzles, cross-referencing zodiac signs, and collecting keys), you’ll regularly be pulled into a cemetery, foggy shipyard, or a swamp with fires burning in the distance. Reality at Decerto is flimsy. It’s cool (and it beats covering the same 10,000 square feet repeatedly) but Alone in the Dark has the bad luck of following Alan Wake 2. In Remedy’s modern masterpiece, new locations and deadly shadows spring to life seamlessly with the flash of a lightbulb. Here it’s more jarring–sudden in a clunky way. It’s still an interesting choice and fundamentally a good thing, but the transitions are noticeably primitive in comparison to its contemporaries.

The controls are standard for a third-person shooter and combat, while nothing special, is passable. So passable it lured me into a false sense of security early on. I spent the first encounters slowly lining up headshots as creatures closed the distance. I should’ve known that this was risky to attempt but I was confident I’d inflict enough damage to drop my target before they entered bludgeoning range. But no, I failed, and there I was embarrassed, pinned at the end of an alley, getting beat on like a sack of meat by a sack of meat.

Speaking of bludgeoning, you also have a melee attack mapped to a shoulder button for finishing or creating space. Weapon durability encourages you to cycle through the available arsenal as your pickaxe or pipe snaps off after only a handful of swings. The assets that clutter the stages turn into a nuisance here. You’ve been smacking eldritch beings with a shovel for hours but you’re only allowed to use SPECIFIC shovels. Throwable objects also blemish the combat arenas. It’s nice to have one more wrinkle in what are otherwise straightforward fights, but they reveal themselves too early and dull the suspense. It’s the same feeling as when you enter a new location while playing a cover shooter and it’s packed with waist high crates.

If it isn’t obvious from the screenshots I chose for this review, the art direction, effects, and graphics frequently come together to create moments of uneasy wonder. Unfortunately, I still ran into a few technical issues. I once sprinted past a trigger to drop down and ended up suspended in midair until I loaded a previous save (Alone in the Dark offers a healthy amount of manual save slots and I suggest you abuse them regularly). More frustrating, I encountered a glitch where anytime I picked up a hatchet in game text would inform me I was “full on hatchets” and delete whatever melee weapon I was carrying–leaving me empty handed (and usually surrounded by things trying to kill me). I promise you, I wasn’t full on hatchets. I never figured out a fix for this. Luckily, the former glitch occurred 80% of the way through the story and as long as I remembered NOT to top off my hatchet supply, I was fine. Apparently, I have a terrible memory.

So should you play it? Yes.

Should you play it twice? That’s a more complicated question.

As I mentioned above, Alone in the Dark offers dual protagonists and invites the player to experience two sides of the same story. This is a bit of an exaggeration. While many of the conversations contain unique dialogue for each character, I rarely came away with a deeper perspective of the events than I did the first time. It’s like reading an essay with different body paragraphs but the same thesis and conclusion. The game tries to make up for this by offering a unique level for both Carnby and Emily–so you’ll need to weigh if that one twenty minute section is worth the retread. My first run clocked in at exactly eight hours (the trophy for eight hours of play time literally popped during the last boss) while my second, with forbidden knowledge of the puzzles and mansion layout, took a little over four. If you decide to take the plunge and experience “the full story” just know those subsequent trips are basically sprints. There are multiple endings to unlock (in fact, I stumbled on to one of the stranger secret endings on my second playthrough), but unless you’re actively pursuing a speedrun world record, the other conclusions are best left to a YouTube compilation.

In what has become the oppressive reality for the video game industry over the last 18 months, Pieces Interactive, the studio that developed Alone in the Dark, was shut down when it “performed below management expectations.” It’s worth mentioning (in the same way when someone is murdered it’s worth mentioning the killer) that these expectations were set by the Embracer Group–a company that gobbles up legacy IPs, dumps them in developers laps, micromanages, mismanages, and eventually cuts staff to celebrate another job well done. Bonuses for all the top brass that don’t make anything! While at this point it’s easy to be numb, these layoffs feel especially tragic because there’s something here. As I established in the introduction, I wouldn’t consider myself a die-hard fan but this is easily my favorite entry in the franchise. I don’t doubt a sequel would have been spectacular. Pieces built the solid foundation of a haunted house. It’s a shame it was being looked after by shitty landlords.